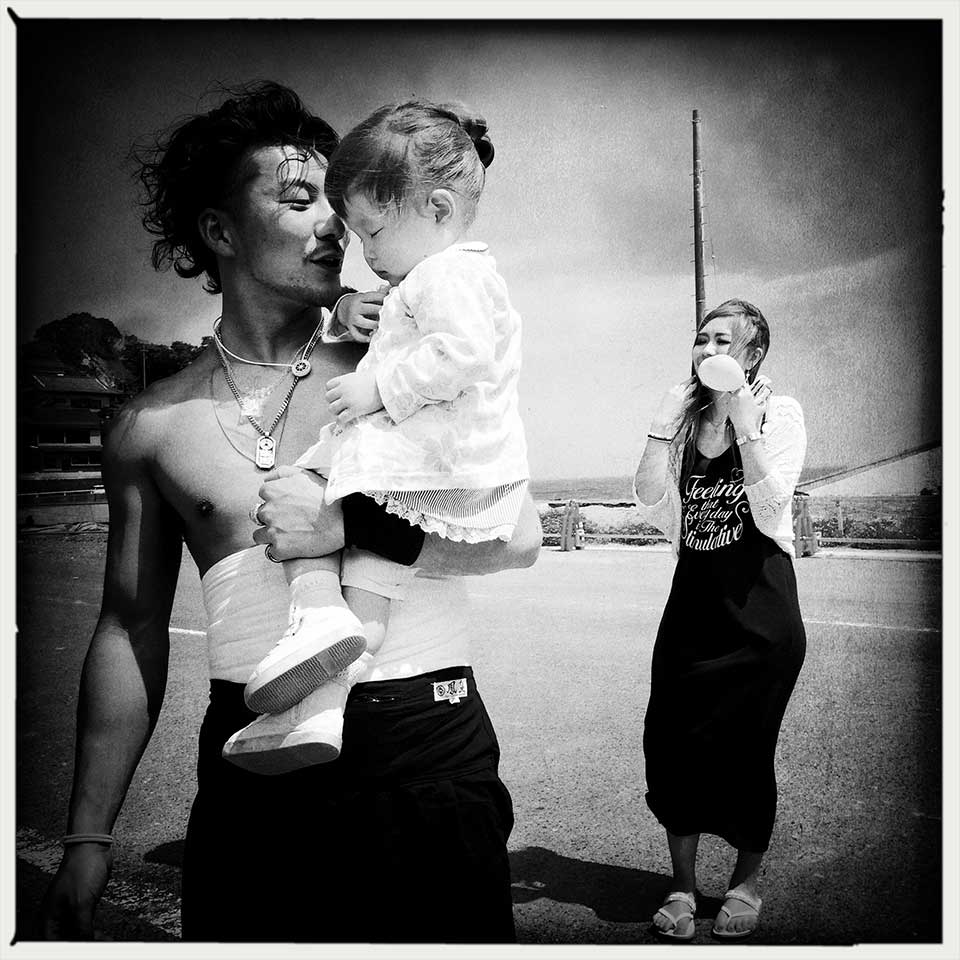

The Elusive Universal: An Interview with Q. Sakamaki

Q. Sakamaki is a Japanese born, New York based documentary photographer and visual artist represented by Redux Pictures. He has covered and captured stories from Afghanistan, Iraq, Palestine, Kosovo, Haiti, Liberia, Sri Lanka, Brazil, Turkey, Georgia, Sudan, The Suicide Forest of Japan, Fukushima, Tibet, and more. He is also very inspiring. By Matthew Wylie

Q. Sakamaki is a Japanese born, New York based documentary photographer and visual artist represented by Redux Pictures. He has covered and captured stories from Afghanistan, Iraq, Palestine, Kosovo, Haiti, Liberia, Sri Lanka, Brazil, Turkey, Georgia, Sudan, The Suicide Forest of Japan, Fukushima, Tibet, and more. He is also very inspiring. By Matthew Wylie

Matthew: You have been known to use the Hipstamatic app for a while now, both in colour and black and white. As time has passed, and most likely change/progress in your own photographic journey as an artist and photojournalist has occurred, what keeps you coming back to this app?

Q. Sakamaki: Fist of all, regarding the change/progress, the view and mind of the photographer is the most important. Then, the equipment or app comes into play. And in that case, especially with the use of the iPhone, I love the Hipstamatic app.

Matthew: And what determines when you choose to shoot with another, perhaps more "professional" camera?

Q. Sakamaki: For the assignments or so, I mostly use the professional DSLR cameras. Yet for my own projects, I often choose different types of cameras -- film (such as panorama camera, 4 X 5, Holga, etc.) to the iPhone camera , depending on the type of the project, as well as my feelings on and for the subjects.

Matthew: One of the photographs I love of yours, among many, is a photograph you took that was the result of the randomized option on Hipstamatic. Do you often rely on chance when using the app?

Q. Sakamaki: That one happened very accidentally. Usually, I preset for the lens and film. My favourite combination is John S + AO BW. Also, I love John S + US1776. Both of those combinations have something similar to shooting in film.

Matthew: Does mobile photography, or even mediums like Instagram, devalue "good photography"? How do you understand this conversation?

Q. Sakamaki: No, I don’t think so. Mobile shooting and/or mediums – not only Instagram, but also large format, such as 4 x 5 -- are just part of the tools to show the photographer’s view. The most important thing, again, comes from the inside of the photographer. Many people think, and I feel wrongly, that mobile photography and Instagram cannot create good photography. Yet mobile photography and Instagram have become very popular. That is why many people think mobile photography and Instagram devalue photography. But again, this perspective is wrong.

Matthew: Approximately a year ago, you spoke with National Geographic about the desire to fuse your own identity with that of "photojournalism" and that you wanted to get to a point that you haven't reached yet. After a year now, and after what I assume have been many interesting explorations around the world (Tibet, Palestine, Japan, Inner Mongolia), I am curious to know how you feel and how you would describe the point you are currently at as a photographer.

Q. Sakamaki: Still on the way. My dream is that I reach some point by catching the invisible, yet universal view that is often behind the viewable subject of the photography, putting forth somehow my own identity, or one related to that of mine.

Matthew: Can you give me an example of this? Who is a photographer who has accomplished this idea of catching "the invisible, yet universal view" - something that is beyond the viewable subject?

Q. Sakamaki: Two examples, though each unique: First - Masahisa Fukase’s book "Karasu (Ravens)." The subject is visually that of birds, but all of them are metaphors of his own. Through the birds and the environments around them, Fukase was exploring and photographing his own darkness, which could be universal for human beings, since anyone has agony, even depression. The other: the photo story of “Invasion 68: Prague" by Josef Koudelka. That one might be more doomed. It was beyond the greatness of the images, since Koudelka himself was Czech and part of the people struggling for their existence. Whether consciously or not, through his work he explored freedom. More importantly, it was also a metaphor of the universal struggle of more than tens of millions of people then within the Soviet controlled Iron Curtain.

Matthew: Has your recognition, for example, via accolades (Emmy nomination, World Press Photo prizes, etc.), changed you as a photographer? I am curious to know how the paradigm of "being known," or having your work seen by so many, affects the way you approach your work, versus how you might have approached it intuitively?

Q. Sakamaki: Such awards have helped me a lot in terms of having assignments or being published; regarding how I have changed as a photographer after those awards, it is actually hard to say, since the bottom line is the same: I have always tried to weigh in with my own style or view. Yet, after many years, such a tendency is growing stronger. And in recent years, I feel the drive to put forth more of a sense of my own identity into my pictures.

Matthew: Can you give us an example of how you feel you have done this in recent years, compared to earlier stages in your work?

Q. Sakamaki: Covering China and Fukushima and further exploring other parts of Japan, such as The Suicide Forest, are examples. I simply feel more of a closeness to my own personal, national, and social identity.

Matthew: Regarding your travels this year, and even years past, how would you characterize the connective thread to what you are trying to do with your work? What is it that you would like audiences to take away that is maybe left unsaid in the rather straight-forward, documentary style captions you provide on Instagram or your own website?

Q. Sakamaki: Nearly always, I would like to explore and share human nature, especially one’s struggle for existence and identity, through the subjects and the environments around them, whether viewable or invisible, that are often overlooked, ignored, or even unseen in standard time or space.

Matthew: You recently visited Tibet. What were some of the challenges or experiences you encountered with there?

Q. Sakamaki: I had to photograph in extremely restrictive situations due to the political, social environments.

Matthew: Did you have one story or location that was most rewarding to you this year?

Q. Sakamaki: This year, Jukai, literally "Sea of Trees ," but often called the "Suicide Forest." Two big reasons. 1st: Japan has, in recent years, had one of the highest suicide rates as a country. 2nd: Despite this fact, Japanese society tends to talk much less about it. The Suicide Forest represents both of the features well.

Matthew: How important is it that you interact with your subjects and the stories you seek to document? Do you ever find conflict in getting too involved, and thus losing the objectivity that is most often associated with photojournalism?

Q. Sakamaki: The interaction with subjects and stories is important, since it aids in reaching human conditions, physically and psychologically. Otherwise, the coverage might be superficial. However, one should have no bias. So far, I have experienced no conflict, even if I got involved more than usual.

Matthew: Do you experience any conflict with artistic expression vs. documenting the world around you?

Q. Sakamaki: Many times. It is very natural to have such a conflict.

Matthew: Oftentimes, I notice that photographers struggle with this and even so much so that they are forced to completely separate the "artistic" work from the "documentary" work. Must the two be separate?

Q. Sakamaki: No. How to make the great combination of such conflicting elements is also a mark of great art and journalism. Photographers (in this case, documentarians) and journalists are not forensic scientists or attorneys. We have to impress people, yet we must do so in the spirit of “non-fiction."

Matthew: Could you talk a bit about the Hikari Creative, of which you are a co-founding member, on Instagram? It's such an inspiring group and so well curated! How did this group form and what are your thoughts on the first year of its development?

Q. Sakamaki: Hikari Creative was created with Iranian photographer Ako’s initiative, and then we brainstormed our common ground for the photo-philosophy. It became: To explore art in human life through photography, importantly any type, from photojournalism to fine art, by creating and curating the images that are shot with a mobile camera. So far, it has gone very well, especially recently, since it is showcasing very different types of great images.

Matthew: In what ways have other art forms (music, literature, painting, dance, film) influenced your photographic work?

Q. Sakamaki: For music, I would mention Pink Floyd. With literature, Yukio Mishima and Junichiro Tanizaki. The paintings of Raphael, Francis Bacon, Syaraku, Hokusai, Lautrec . The dance of Pina Bausch, the films of Godard, the filmmaker John Singleton (Boyz N The Hood), and so much more.

Matthew: You have documented a number of places and areas that are, with all due respect, rather well documented by photographers, such as Palestine, Sudan, Burma, and so on, though, unfortunately, the actual stories of the places, rather than hyper-coverage, are too often under-represented by the media. However, you have also done quite a bit of work from your native country, Japan. I am extremely curious what you have to say about the representation of Japan's 21st century stories, either from the media's view, or your own attempts to cover said stories, e.g. Fukushima, The Suicide Forest, and more.

Q. Sakamaki: Both Fukushima and The Suicide Forest represent Japan's 21st century society. For Fukushima, it is not just because of the nuclear power plant accident itself, but because of the reasons why the nuclear power reactors were put there in the first place, e.g. a depopulation and shrinkage of job markets in Japan’s countryside. Both Fukushima and The Suicide Forest have been less and less covered, as the time has passed, despite the continuous importance of each.

Matthew: Thank you, Q, for the interview (that rhymes). If you will indulge me, I would like to conclude with a set of questions designed, originally, by Marcel Proust, one of my favourite authors.

What is your favourite word? Hope What is your least favourite word? Nonsense What inspires you? Travel What robs you of inspiration? Wrong incoming call What sound or noise do you love? Those created by waves and wind. What sound or noise do you hate? Scratching on the glass What is your favourite curse word? Italian way of “fuck your ass hole” -- I don’t know the spelling. What profession, other than your own, would you most like to attempt? Film Director What profession, other than your own, would you least like to attempt? Banker If heaven exists, what would you like to hear God say when you arrive? I don’t believe heaven. So, I want to hear “Don’t worry. You can enjoy here, too.”

This post is also available in: French

0 comments